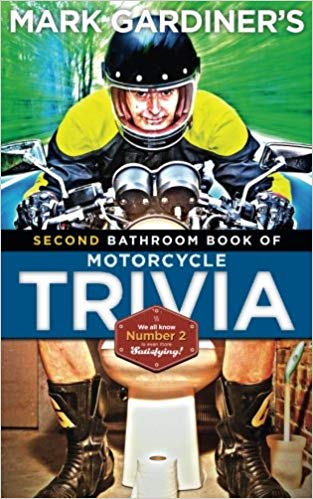

This text is excerpted from my Second Bathroom Book of Motorcycle Trivia. (The first Bathroom Book of Motorcycle Triviawas an Amazon best-seller, but let's face it: we all know that when it comes to reading on the john, 'number two' is even more satisfying.)

Over the years, a few English motorcycles have been sold as Indians. And from 2006-’11, the Indian Motorcycle Company was owned by a London-based private equity firm called Stellican Limited.

Stellican bought the brand and assets from the Gilroy company and produced a small number of motorcycles out of a new home in Kings Mountain, NC.

Although some of the transactions were spurious (or do I mean ‘scurrilous’? Maybe both...) Stellican was approximately the 18th company to own the Indian trademark. The company had previously resurrected another iconic American brand, Chris-Craft.

Stellican relaunched Indian in 2009, but sold less than a thousand bikes.